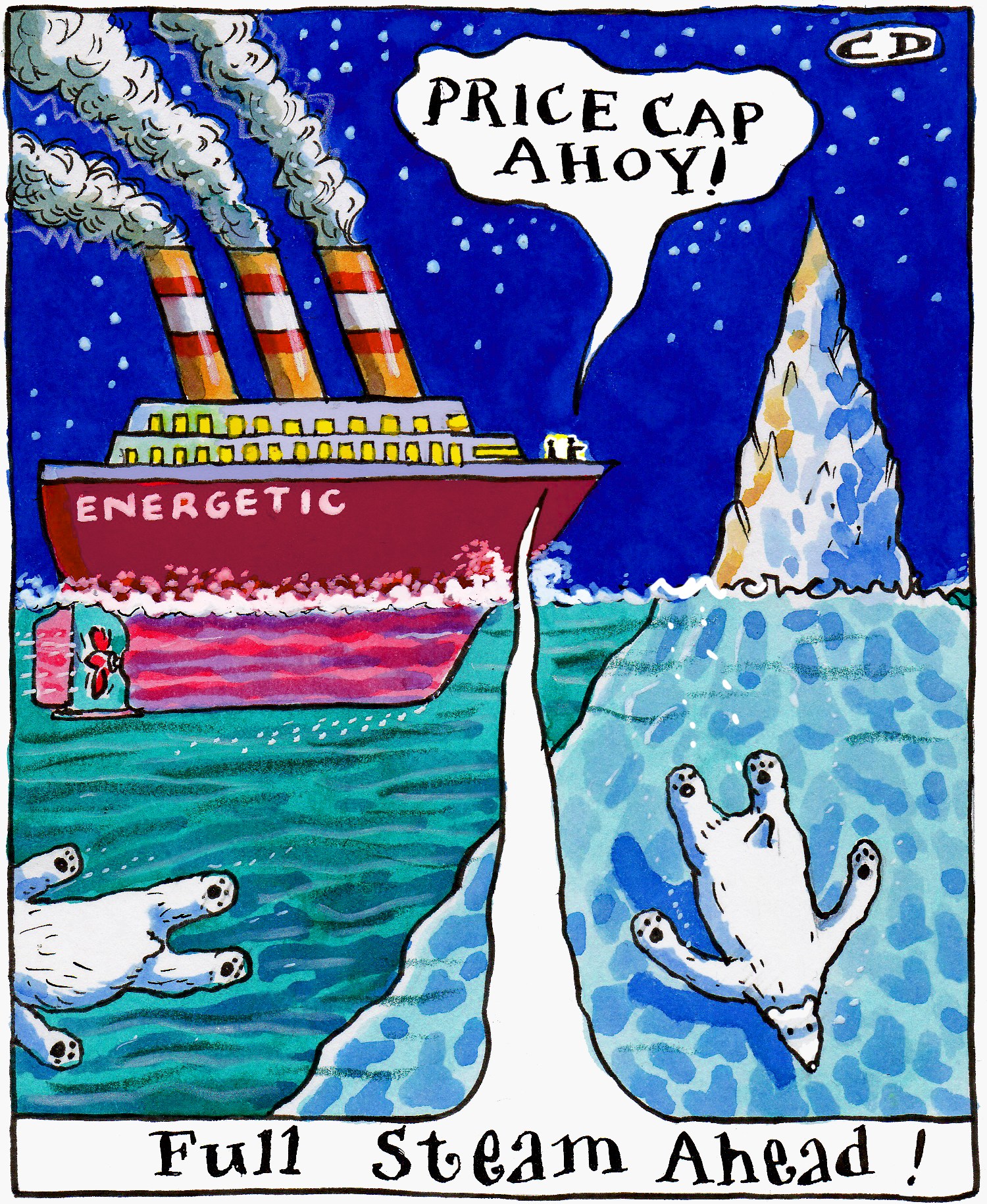

Fatal flaws are often found out only in extreme circumstances. Who knew that the Titanic’s watertight door system would not work as advertised, until it hit an iceberg? Who dreamt that a Concorde tyre might explode if it ran over a strip of metal, rupturing a fuel tank in the wing above and setting the aircraft on fire?

So it is with the cap on energy bills, an idea cruelly exposed by the rapid rise in wholesale electricity and gas prices. The retail market has been plunged into chaos, with 29 suppliers going under (adding about £2 billion to bills) and four million customers having to be shunted to new companies or, in the case of one of the largest failures, left in a kind of taxpayer-funded limbo until something better turns up. The difference between the Titanic and the price-cap plan, though, is that the naval architects of the time thought the ship’s design a step forward and were doing their best to improve things, not make them worse.

That is not the case with the price cap. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) did a deep dive into the energy market six years ago, trying to tackle the perception — and, often, the reality — that energy bills were simply too high. Customers who stayed with the same provider year in, year out, often ended up paying much more than they should. The conclusion was that a general price cap was a bad idea. “The majority of us,” the competition wonks said, “believe that attempting to control outcomes for the substantial majority of customers would, even during a transitional period, run excessive risks of undermining the competitive process, likely resulting in worse outcomes for customers in the long run.” They also found that problems in the energy market were largely down to inefficiencies, not excessive profiteering. “If we were to eliminate the entirety of the detriment we have observed through a price cap it would create substantial losses for the sector as a whole.”

That was an excellent prediction of what has happened over the past six months. It should be obvious that if you set a cap on retail prices in a market where wholesale prices can swing rapidly, the companies caught in the middle can be squeezed to oblivion. There was even, if the CMA had chosen to cast its mind back four years, an example of how nasty the energy market could be. It was the present process in reverse: British Energy, the operator of Britain’s nuclear power stations, had to be bailed out by the government after wholesale prices collapsed, leaving it with a yawning gap in its income.

None of this troubled Ed Miliband, who made a price cap part of Labour’s 2015 election manifesto. David Cameron said this proved that Miliband lived in a “Marxist universe”, but the idea polled well and made it into the Conservative manifesto in 2017. Theresa May followed through on the promise and the first cap came into effect in 2019. It was an interventionist play in a system that until then had been extremely laissez-faire: the guiding light had been the introduction of increased competition to flog the fat off the big six energy companies that were seen unfairly to control the market. Ofgem let a thousand flowers bloom. The two policies did not mix well and undercapitalised energy companies on the wrong side of the cap have gone to the wall in droves.

Yesterday Ofgem came up with a plan to try to fix this regulatory mismatch: tougher financial stress tests for suppliers and more frequent changes to the level of the cap. Once you start tinkering with retail prices you are forever going back to try to keep up with events, as successive Labour and Conservative administrations found in the 1970s.

The politicians who introduced the cap liked the idea of shielding customers from higher prices. The past week has proved that it cannot do that. It has instead only hidden many people from the reality. We are at the mercy of the international markets that set the price of oil and gas, upon which, despite big investments in renewable generation, we rely to keep the lights on. The burning of fossil fuels, mainly gas, generates about 40 per cent of our electricity. Futhermore, the cost of the eventual transition away from fossil fuels is going to be greater than most think and it will be paid for by customers through higher bills.

The cap was designed to be a short-term measure. It is due for review next year and Ofgem must tell the government if market conditions are suitable for its removal. What “suitable” means in this respect is a good question. Does it mean, as it should, that there is sufficient competition in the market to be sure that customers are paying fair prices? Or does it mean that prices have fallen far enough for the removal of the cap to be politically palatable?

Given that the cap was a political measure in the first place, the latter answer is more likely to be the correct one. Gas prices are likely to stay high, and certainly volatile, for the foreseeable future. Not only is tension between Russia and the West over Ukraine stoking the market but there are longer-term factors at work. Big industries in eastern Europe and Russia are starting to shift from coal to gas in an effort to cut their carbon dioxide emissions, bringing a whole new group of large customers to a tight market.

That means that the cap is likely to be with us for a while, and with it regular injections of government money to keep retail prices down. Another way of thinking about this is that only a few months after Cop26 ministers are subsidising the consumption of fossil fuels. At forums like the Glasgow climate talks, leaders are happy to talk about rising fossil fuel prices helping the shift to greener forms of energy. That has been the case for many big UK businesses, which have pleaded with ministers for help with energy and carbon costs but been given short shrift. When the reality of rising prices and dealing with climate change starts to affect millions of voters, however, money can be found.

Dominic O’Connell is business presenter for Times Radio